“Those who rush ahead do not travel far.” — Tao Te Ching

Morning smog settled over the park like a silken veil, blurring the lines of the open field and turning it into an intimate classroom. The space let posture speak louder than intention, and mistakes surfaced without argument. I arrived early, not to mark territory but to read conditions: cool, damp air filled my lungs, stiffness lingered in my hips and shoulders, and echoes of yesterday’s work buzzed just beneath the skin. Training always begins before instruction, long before a student throws the first punch or asks the first question.

I opened the session the way I always do, with order rather than urgency: joints before jumps, alignment before aggression, breath before bravado. Wrists rolled under control, elbows circled without strain, shoulders loosened while staying connected, the neck unwound slowly so awareness stayed online instead of drifting upward into performance. Then hips opened, knees tracked, ankles woke, each rotation reporting what the body carried forward and what today would demand payment for. These early minutes rarely impress students, yet these minutes decide the tone of the entire session, because structure earned early saves energy later.

When things drift, escalation adds friction, while a return to root conditions restores control. — I-Ching 24, Return

From there, we moved into finger-up push-ups, not for toughness theater but for hand integrity, building pressure tolerance while keeping sensation intact. The drill teaches the wrist to withstand sudden impact, a key demand in martial training. I had him count rounds out loud so attention stayed present and effort stayed honest. We dropped next into low horse, thighs heating, breath tightening, posture negotiating with fatigue, and I ran him through a six-position drill, shifting angles without excess travel, learning the difference between movement and fidgeting, between changing position and changing power. Every training session eventually asks one question, whether the student hears it or not: Can structure hold while pressure negotiates for shortcuts? That question waited quietly until the punching began.

We moved into straight punches, then inner-gate and outer-gate lines, then chain punches, not as frantic volume but as cycling strikes fed by hip rotation, elbows heavy, wrists aligned, knuckles traveling along a clean line. The body organized well enough to matter. Contact arrived, and with it, the lesson surfaced immediately. He touched the line—range close, timing close, structure close—then habit intervened. Instead of adjusting from contact, he pulled back to reset, stepping out of range to restart the drill as if safety lived behind him and information lived ahead.

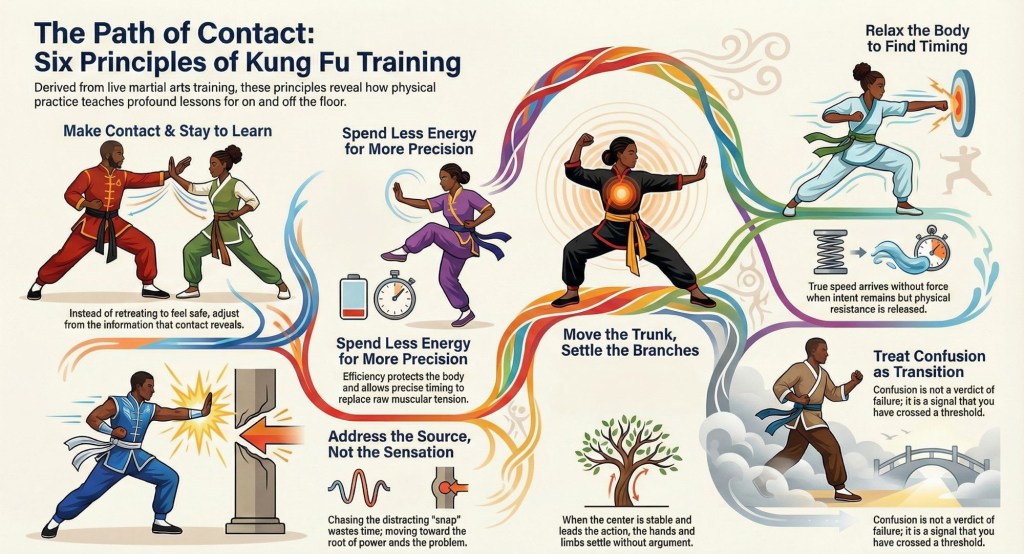

I stopped him on that exact beat, the moment where training either deepens or repeats itself, and gave the correction welded directly to the body in front of me: don’t pull back—finish from contact. A memory from my early training surfaced, a sparring exchange where I instinctively stepped back and left an opening my opponent exploited without hesitation. The lesson clarified itself: Abandoning contact meant abandoning the opportunity to learn and adapt. In Wing Chun terms, once the bridge forms, you don’t abandon it just to feel prepared. Contact delivers information—pressure, direction, imbalance—and pulling back discards that intelligence. The body then pays twice, first for the lost opening and again for the energy required to recreate timing. Students often call this reset “discipline,” yet discipline should look like adjusting from reality rather than restarting from fear. Laozi warns against unnecessary retreat and excessive striving, and that warning lands plainly here—stay with what happened long enough to let it teach you.

Abandoning contact meant abandoning the opportunity to learn and adapt.

Fatigue crept into the session, effort rose, and efficiency dropped. Shoulders climbed, breathing shortened, punches grew louder while accuracy thinned. I didn’t correct intensity; I corrected waste. I reminded him to use the least amount of energy required to get the result, not as a softening move but as a sustainability move. We dropped punch power to fifty percent and cleaned structure. The hip fed the hand, the elbow stayed heavy, and the strike landed cleaner because timing replaced tension. Efficiency protected wrists and shoulders, preserved the nervous system, and left enough capacity for the rest of the session and tomorrow’s work. Kung Fu never rewards exhaustion for its own sake; it rewards precision under conservation.

We shifted into elbow work—sink elbow, front elbow, recovery—and the snap triggered flinches. Shoulders rose, eyes blinked, and the body reacted to noise instead of mechanics. I introduced the next correction while the problem still lived in the body, reminding him to move toward the source, not the snap. The whip cracks loud at the tip, yet power lives near the hand. Like judging a storm by thunder instead of pressure change, chasing the crack wastes time, while closing toward the source ends the problem. In training, the snap shows up as flinch and tension, and the correction lives in breath dropping, ribs settling, hips turning. When the source aligns, the snap loses leverage. of I Ching Hexagram 24 ‘Return’ names the same motion: when things drift, escalation adds friction, while a return to root conditions restores control.

As rounds continued, the hands sped up without clarity, fluttering independently of the body, announcing effort while losing control. I didn’t argue with the hands. I moved the trunk. Stance widened slightly, shoulders softened, breath dropped, and hip rotation slowed and deepened. The hands settled without instruction because the center reclaimed leadership. Students often fight symptoms—slow reactions, frustration, uncoordination—while ignoring root conditions such as focus, posture, rhythm, and sensitivity. Training exposes this immediately. Move the trunk and the branches follow.

When things drift, escalation adds friction, while a return to root conditions restores control.

Mid-session, sweat rising and corrections stacking, he said the line every honest beginner says sooner or later: “I’m losing it.” I translated rather than reassured. Learning often feels like loss when old coordination dissolves and new timing hasn’t stabilized yet. The mind releases control before the body claims competence, and fog fills that gap. That fog signals entry into real training. The I Ching describes this phase repeatedly—return before advance, patience before clarity. This moment mirrors a familiar passage in training, where confusion marks transition rather than collapse. If confusion shows up here, the student didn’t fail; the student crossed the threshold.

Move the trunk and the branches follow.

We closed the session with the correction that protects joints and sharpens timing at the same time: relaxation generates speed. I coached mechanics rather than mood—jaw unclenching, shoulders dropping, elbows loosening, hips turning. As we ran chain punches again through a quieter body, knuckles hummed like tuned strings, resonating with a rhythm that spoke of both control and freedom. Speed arrived without force because rotation traveled cleanly. Intent stayed present while resistance left. Softness kept options open and allowed timing to arrive without strain.

I left Ken Malloy Park carrying the same corrections we worked through during the hour, not as slogans but as training notes written into the body. Teaching always works that way for me—my voice instructs the student while my ears instruct me, catching echoes of the same habits I correct in others when they surface in my own training and daily conduct. Every time I say finish from contact, I hear it aimed back at moments when retreat tempts me more than response.

Return before advance, patience before clarity.

So I keep the practice concrete and repeatable, the way martial knowledge prefers it. I make contact and stay in range long enough to learn, spend less energy so precision can show itself, address the source instead of chasing sensation, move the trunk so the branches settle without argument, treat confusion as a signal of transition rather than a verdict, and relax the body so timing can arrive without force—principles that don’t ask for belief but ask for repetition.

Run them on the mat, in forms, in sparring, and let experience confirm what instruction only points toward. Training does its job when repetition teaches what words only gesture toward. Which drill will you test these principles in today?

Stay inspired… and stay inspirational.

— Sifu Khonsura Wilson