Early morning

In martial arts training, boredom often masquerades as failure, slipping in quietly and convincing practitioners that repetition without sensation means stagnation, that uneventfulness signals decline, that something essential has stopped happening.

When a drill begins to feel dull—no edge, no spark, no sense of arrival—the reflex arrives quickly, urging more speed, more force, more complexity, anything to restore the feeling of effort and confirm that work still counts. That reflex usually misreads the moment.

Boredom often marks the point where ego loosens its grip and the nervous system, unbothered by display, begins learning in its own way—through repetition, through settling, through small adjustments that don’t announce themselves. This isn’t metaphor but physiology.

As novelty fades and threat dissolves, the body’s questions change. The loud concerns—Is this impressive? Is this fast enough? Am I advancing?—fall quiet, replaced by a simpler inquiry, asked without words: Can this hold together without interference? That shift, barely noticeable from the outside, separates performance from maintenance, effort from durability, doing from sustaining.

“Boredom often marks the point where ego loosens its grip and the nervous system begins learning quietly.”

Late Morning

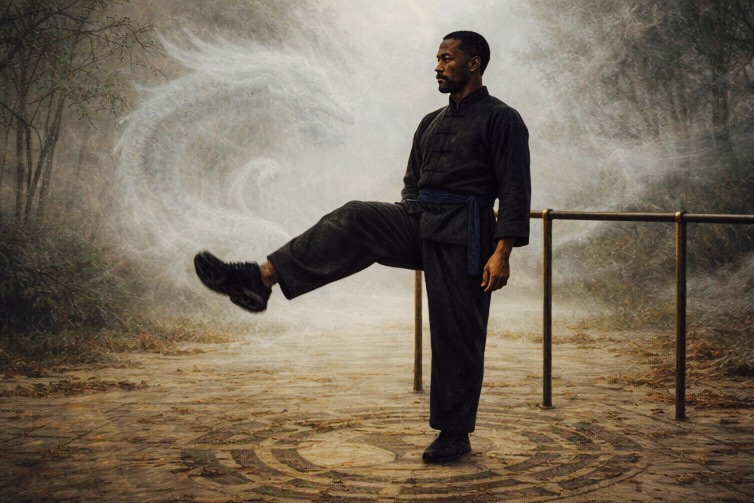

High-rep leg swings make this shift unavoidable. They offer no spectacle, no reassurance, no visible payoff. The movement stays simple, the rhythm repetitive, the outcome stubbornly unchanged. Swing follows swing without commentary, without climax, without reward.

Nothing dramatic arrives. No burn confirms effectiveness. No fatigue certifies progress. Each repetition feels much like the last, and that sameness begins to unsettle the part of the mind that expects evidence. And yet, something organizes.

The standing leg, bearing responsibility without complaint, learns endurance without tension. Balance adjusts through quiet micro-corrections, too subtle for conscious control. Timing emerges by yielding to gravity rather than interrupting it. The nervous system, rep by rep, confirms what tension once questioned—that looseness doesn’t equal collapse, that range doesn’t invite danger.

Attention stays present without hovering, engaged without supervising, allowing learning to proceed without commentary. The work continues, but underground. What remains on the surface feels empty. But emptiness doesn’t signal absence. It signals reduced noise.

“The work hasn’t stopped. It has moved underground.”

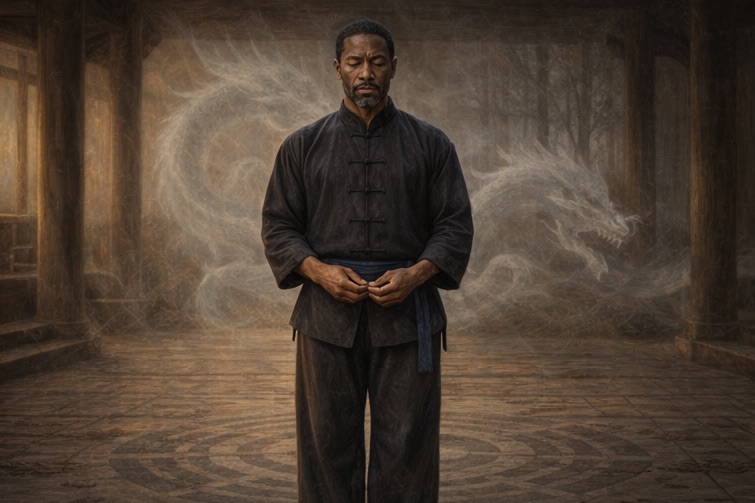

Standing practices extend the same lesson, with even fewer concessions. Horse stance, zhan zhuang, standing meditation—these practices remove motion and novelty altogether, leaving nothing but structure, breath, and attention exposed to time.

There’s no visible progress minute to minute, no metric to lean on, no cue to reassure the ego that something worthwhile unfolds. The body stands, weight settles, breath moves, and the mind, deprived of stimulation, begins searching for reasons to leave. This searching often gets mistaken for insight.

But standing practice doesn’t train movement. It trains organization under stillness, conditioning the body to remain coherent without fidgeting, without narration, without escape. Structure holds. Breath flows. Attention rests, learning how to stay without gripping. The question underneath the posture grows clearer with time: Can presence remain when nothing demands response?

Most people abandon standing not because it overwhelms, but because it refuses to entertain. Those who remain recognize uneventfulness as a sign they’ve crossed into a deeper layer of training, where strength hides inside alignment and power stores itself quietly, without display.

“Standing practice doesn’t train movement. It trains organization under stillness.”

Afternoon

This same intelligence explains why monks repeat mantras, why breath counts cycle endlessly, why sound loops without development or conclusion. Not to add meaning but to occupy what would otherwise interfere.

A mantra gives the mind a simple task—sound without story, rhythm without outcome—absorbing the impulse to comment, evaluate, and supervise. Silence invites interpretation. Repetition narrows attention just enough to keep it present without letting it interfere. The mantra doesn’t deepen the practice directly. It protects the depth already there.

The same principle applies when listening to an audiobook during leg swings. The story occupies impatience and self-commentary, keeping the ego engaged elsewhere while the nervous system integrates. This isn’t distraction from training; it’s distraction for training, a form of attention hygiene learned long before it earned a name.

“You’re not distracting yourself from training. You’re distracting the ego away from interfering with learning.”

Evening

Modern habits resist boring work because stimulation gets mistaken for effectiveness, sensation for progress, fatigue for proof. When boredom appears, the assumption follows quickly: the drill has stopped working, intensity will restore meaning, effort must increase to justify time. More often, boredom signals the opposite. Nothing remains to impress.

This pattern repeats beyond martial training. Writing often feels boring while it’s forming. Thinking feels boring once clarity replaces struggle. Relationships feel boring when stability replaces drama. Health routines feel boring because they work quietly, without demanding notice. Boring practices tend to endure.

Returning where the day began, leg swinging freely while the standing leg works invisibly, breath counting itself while posture organizes without instruction, the scene hasn’t changed. What has changed lives inside the body—the willingness to stay when nothing performs, the patience to let learning continue without applause. Nothing announces arrival but your body will soon confirms it when you do.

“Boredom isn’t the absence of learning. It’s the moment learning no longer needs supervision.”

Stay inspired and inspirational.

Sifu Khonsura Wilson