“The sage dwells in the depths where others do not look.”

The question arrived without ceremony, the way real questions usually enter—through an ordinary doorway, carried by a casual voice, unnoticed until it rearranges the room. Someone asked where the mind lived. The answer came quickly, almost reflexively, shaped by diagrams, schooling, and habit: in my head. Then the questioner paused, not to correct but to widen the frame, and said something that refused to leave once spoken: the mind lives in every cell of your body. The sentence didn’t argue, didn’t persuade, simply waiting.

I carried it with me for days, letting it walk beside small rituals and unremarkable moments—tea poured in the morning, breath settling before sitting, the weight of my body meeting the floor—until it loosened an assumption I hadn’t realized had hardened. Because once the mind no longer occupies a single room behind the eyes, the way most of us meditate begins to feel oddly incomplete, like searching for lost keys only beneath the streetlamp because that’s where the light falls, not where the keys slipped.

“Before enlightenment, chop wood, carry water. After enlightenment, chop wood, carry water.”

Zen Quote

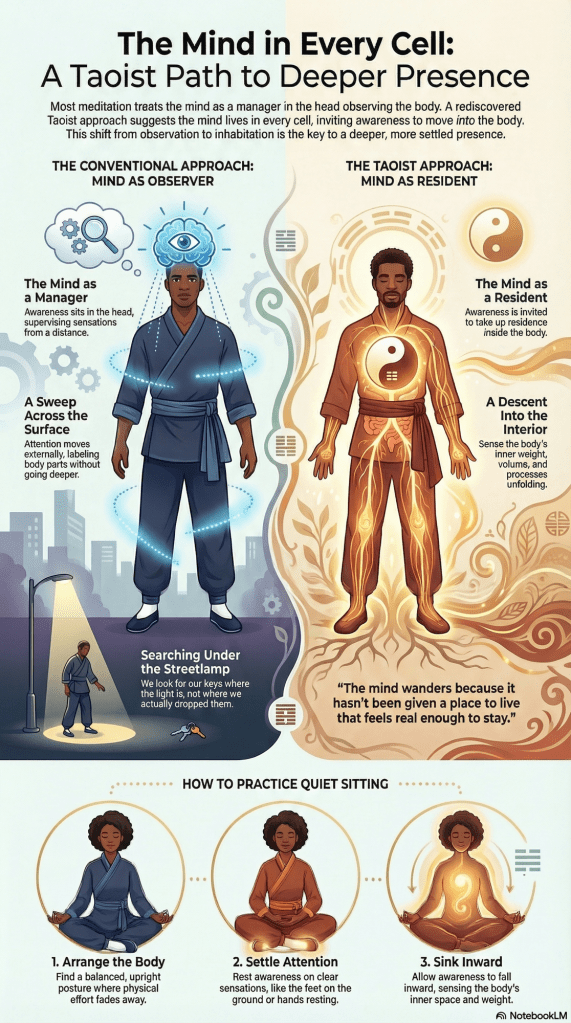

Most meditation instruction still privileges a quiet hierarchy, awareness perching somewhere in the head, monitoring thoughts, supervising breath, checking sensations the way a manager checks stations on a factory floor. Body scanning enters as a corrective, a familiar method meant to tether attention to sensation, interrupt mental drift, and keep awareness closer to what actually unfolds now. It steadies. It calms. And yet, in its common form, it often stops at the threshold of its own depth.

We name the feet, the calves, the knees, relaxing the shoulders, softening the jaw, smoothing the brow, while attention moves efficiently across the body’s surface, collecting sensations like labels on a map. Useful, calming, therapeutic—yet still external, still observational, still faintly removed.

What rarely gets taught—and what kept tugging at me after that casual exchange—requires a deeper turn, attention stopping its lateral sweep across the body and learning how to move into it instead. The difference resembles the one between studying the floor plan of a house and finally sitting down inside it, letting the walls, weight, and silence register without commentary.

A rediscovered body scan doesn’t ask the mind to notice the body. It invites awareness to take up residence inside the body, noticing from there, a shift that changes presence not through effort but through gravity.

“Returning is the movement of the Tao.”

The Tao Te Ching gestures toward this without instruction when it observes that the sage dwells where others do not look, inhabiting what seems empty yet holds everything. Presence follows the same logic, awareness sinking from the obvious vantage points into what usually gets ignored, stillness arriving without command.

The scan begins at the edges, not because the edges matter most, but because they offer easy entry—hands resting, feet touching the ground, the face exposed to air—places humming with sensation, alive with nerve endings, honest in their feedback. Awareness settles there first, not analyzing, not narrating, simply resting the way a hand rests on a table once it stops searching for something else to do.

“The body knows the way. The mind learns by following.”

Zen

Now attention does something unfamiliar, not as metaphor nor imagination, but descending the way breath descends when it finally drops below the collarbones, the way a carried weight settles once the effort of holding it ends. Awareness passes through skin, through the thin electric layer where the body meets the world, and enters the quieter interior where experience loses its sharp outlines. Muscles reveal themselves not as shapes but as density and tone. Bones register not as images but as support and compression. Space inside the body announces itself not as empty or full, but as actively inhabited.

At this depth, thought loses its advantage, commentary thinning because sensation keeps changing faster than language can track. The mind doesn’t quiet through suppression, but through irrelevance, attention sinking so fully into sensation that commentary loses its footing. Awareness stays present because the body offers too much real-time information to abandon.

“When walking, just walk. When sitting, just sit. Above all, do not wobble.”

Zen

Zen practice points here indirectly, insisting on posture before insight, on sitting fully before understanding. Sit correctly, Zen teachers say, and the mind settles where the body settles. Try to manage mind directly, and it slips away, presence responding not to command but to alignment.

As attention continues inward, the scan stops organizing itself around parts and begins orienting toward processes. Breath doesn’t move in the body; breath moves the body, organs shifting subtly with each inhale, circulation pulsing along its routes, steady and indifferent to opinion, balance adjusting continuously without consultation. The body reveals itself not as an object one inhabits but as an event unfolding continuously, inviting participation rather than observation.

Here, the original question begins dissolving.

Where does the mind live?

The I Ching answers without answering, reminding us that observer and observed arise within the same field, that change and awareness share one movement. When attention distributes itself throughout the body, mind no longer occupies a single seat of authority, diffusing through sensation, inhabiting weight and volume, listening from everywhere it touches at once.

Presence stops feeling like a task and begins arriving as occupancy, the kind that comes from finally sitting down after years of pacing, letting weight settle, letting movement finish. This explains why so many people struggle with meditation while blaming discipline or distraction, the difficulty rarely coming from unruly thoughts but from asking awareness to float without a home. The mind wanders because it hasn’t been given a place to live that feels real enough to stay.

Deep body scanning provides that place, not as a technique to master nor as a performance of calm, but as a return from abstraction. Attention repatriates itself from planning, rehearsing, and narrating, reentering the organism that already knows how to breathe, balance, digest, and respond without commentary, what the Tao names returning to the root, the quiet power that precedes effort and outlasts force.

“Do not think good. Do not think bad. See what remains.”

Zen

Modern life trains people to live from the neck up—screens, schedules, language, reaction—while teaching them to ignore the body until it protests through fatigue, tension, or breakdown. A rediscovered body scan doesn’t reject thought; it restores proportion, thought resuming its place as one expression within a larger intelligence already underway.

Presence deepens not through silence, but through descending, attention moving downward and inward, settling where effort no longer leads. The mind doesn’t need to disappear. It needs a place to dwell. The body, patient and uncomplaining, has waited the entire time.

“The Tao never acts, yet nothing remains undone.”

Quiet Sitting: Instructions for the Beginner

Quiet sitting doesn’t begin with insight. It begins with arrangement.

Choose a seat that allows the spine to rise without strain, a chair working, a cushion working, the floor working if the hips lift slightly above the knees. Let the feet or legs settle fully, making honest contact with the ground. Upright doesn’t mean rigid. Upright means balanced, the way a stack of stones balances because each stone trusts the one beneath it.

Let the hands rest where they naturally fall. Let the shoulders hang. Let the jaw release its habitual grip. Adjust until effort fades, not until posture looks correct.

Now let attention touch the body where sensation speaks most clearly—feet, hands, points of contact with the seat—without searching, letting sensation announce itself. Warmth, pressure, tingling, absence—everything counts, nothing requiring correction.

When attention feels stable, invite it to sink inward, not by pushing nor visualizing, but allowing awareness to fall the way breath falls when it stops climbing the chest and begins filling the belly. Sense the body beneath the skin. Sense weight. Sense volume.

If the mind wanders, notice where it wandered from rather than what it wandered to, bringing attention back to the body the way one returns home after stepping outside briefly—without judgment, without commentary.

Let breath move naturally. Don’t follow it. Let it follow itself. Notice how each inhale gently shifts the body, how each exhale returns it, quiet work happening without instruction. Sit for five minutes at first, ten when the body asks, longer when stillness invites rather than challenges. Quiet sitting doesn’t demand success. It rewards sincerity.

“The noble one returns to stillness. In order to understand movement.”

I-Ching

Which brings me back to that opening moment—the question asked in passing, the answer given automatically, the pause that followed. When someone says the mind lives in every cell of the body, they don’t offer poetry for poetry’s sake. They point toward a way of living, suggesting that presence doesn’t hover above life, judging and managing, but lives inside it, breathing where breath already moves, standing where weight already settles, listening where sensation already speaks. The question still sits in the room. It simply no longer needs an answer.

Stay inspired and inspirational.

— Sifu Khonsura Wilson